I have recently read a number of books involving gardens. It began with Salley Vickers’s The Gardener and was quickly followed by The Secret Garden and Tom’s Midnight Garden. This prompted a degree of feverish activity in my own hapless plot and a great deal of time spent in a gardening encyclopedia, researching how to care for the plants I have been subjecting to half-understood practices and my own whimsy. My garden is the better for it, and so, I think, am I.

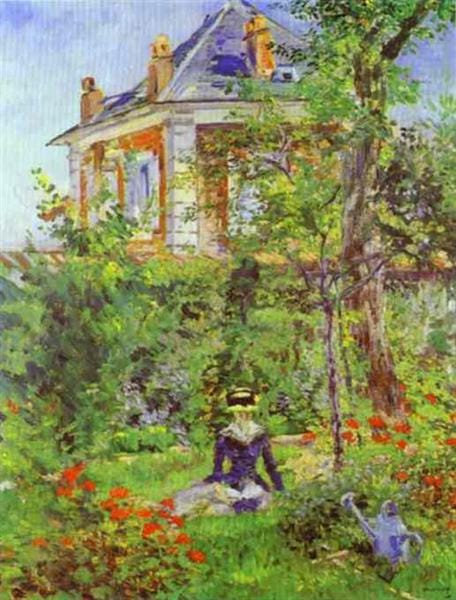

As all three of the books I’ve just mentioned (particularly the first two) explore in their own ways, the garden is a place in which immense healing can occur and well-being nurtured. It is a place where one feels something at work, a mystery of subtle but, the more one encounters it, incredible significance. The garden is, in fact, a place where one is continuously brought in contact with something apparently more than the quotidian, a rustle or breath of presence beyond the scope of what one normally encounters. This is not just the fascination of growing life, although it certainly includes this—there is something more at work, something extending beyond the realms of the physical.

The garden is a meeting place of two worlds: the human world and another, less easily defined world, a world that is perhaps multiple or farther reaching than can be simplified into a single name or category. One of course encounters the vegetal, and frequently the animal, as well as the mineral as it flows beneath one’s fingers and tools in the heaping and running soils and composts, border stones and rock features. Yet these creatures are themselves but the emissaries of yet deeper mysteries. The Magic of the Secret Garden is manifest in the sproutings of the bulbs and roses, the seeping light of springs and wellness, but it is not reducible to them, for it is a flicker of the transcendent, of the divine life that breathes its way into and through all being. Nor is it any accident that Halcyon’s garden in The Gardener edges a faery-haunted wood. The other, the unseen is felt in the garden, a doorway or meeting place upon a border to the mystery, whichever mystery, perhaps all of them, if one has the eyes to look. Tom’s garden, too, is a meeting place, not of faeries or the cosmic pneuma, but of other times, of personalities that, though distant, resonant with sympathies that bridge decades. It is only natural that Tom (the present-day protagonist) meets Hatty (herself a Victorian) through a garden, through the gateway opened by the angel, that the deeper currents of the soul pulse and become visible.

Of course, all gardens harken back to that first garden, Eden, which is itself frequently paralleled to the New Jerusalem. This transition from garden to city is perhaps banal at this point, but it is worthy of this regard, for it manifests the identity of the garden and the city. The city is, at its best, a garden perfected, a way of existing in cosmic harmony, every piece organized perfectly along the microcosmic structure of humanity. It is, in fact, the perfect correspondence of the cosmos and the human soul in the realization of the heavenly life, each in its place, from the precious stones of the streets to the central tree and households of the inhabitants. Every level present and accounted for, perfectly integrated, the city and the garden as one. The distinctions begin to fall apart because the embrace is so complete.

This image is ultimately an erotic one, for it is, as I have said, one of loving embrace, of the earthly and the heavenly—or the natural and the artificial, the wild and the orderly, the water and the sun, the soil and the seed. All difference is here resolved in a mutuality of desire and recognition; each is a lover and joins arm in arm with the fertility of marriage. This is in a nascent way the meaning of Eden and in a yet more mature sense the meaning of the heavenly Jerusalem.

So, I think, the garden is in a very real sense a place of marriage, a marital bed, in fact, and so a place that is essentially erotic. It is because of this that the garden as a place in the imagination, and so in literature, becomes a place of meeting, of healing, of the in-breaking of the transcendent and the uncanny. It can be this in literature because it is so in reality—the garden pulses with life unknown and yet recognizable in its strangeness, for that which is beyond one’s scope is here invited in and given a place to rest and live, to flourish and bloom fertile ekstasis and, like Adam, produce its blood and bone from out its dreaming side. We find, like Colin in the secret garden, ourselves, for by uniting everything, we, the world in miniature, are brought together, are integrated. Should this become not just the work of a few backyard plots and quiet, enterprising hands, but the task of all, the city-garden might be born and put forth blossoms. Then, perhaps, we would free ourselves from crooked spines and dull surroundings and meet, at last, the faeries living at the edges of our lives.